Glass Promises

I swear by Apollo Physician, by Asclepius, by Hygieia, by Panacea, and by all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will carry out this oath, according to my ability and judgment.

Thus opens the Hippocratic oath, a code of ethics sworn by doctors though the centuries. Legend has it that this oath was composed by the Greek physician Hippocrates, active around the fourth century b.C. Legend also has it that Hippocrates was the direct descendent of the Olympian god Asclepius, the god of healing and medicine. And while we may agree that these are just legends, it is also true that legends are precisely such because they hide a kernel of truth. The truth of this particular legend is that medicine is a gift of the gods.

The point I want to make, however, is not really about the gods at all. The gods simply function as placeholders, as all-too concrete personifications of an objective order of values, inscribed into the very order of nature. Other philosophical systems tailored their own oaths. Some swear at the feet the Buddha; others before the God of Abraham. In all of these oaths, medicine is put in relation to the rest of reality: to the objective order of values, to the supernatural, to the doctor's fellow creatures. Medicine is always placed within an over-arching worldview.

Another striking aspect of these oaths is their similarity. This includes the unanimous condemnation of euthanasia, as well as a ban on abortifacient herbs and potions. Hardly many doctors in the West would sign up to these restrictions today. The course of history has eroded these previously sacred values. But, at the same time, history has also eroded the very ground on which all these values stand. The story about reality in which they previously found their justification has withered away. The defining feature of our (post)modern society is precisely that we lack any such over-arching story about reality and our place within it. Our world is no longer crawling with spirits and deities, tasked with upholding the moral order of the universe. Nor – as in the world of the descendants of Abraham – is everything under heaven allotted its proper place, from the stars in the heavens to the sand-grains on the seashore, under the vigilant gaze of Providence. All of which begs the question: how are we to ground bio-ethical values today? Are they anything more than a mere convention, a historical accident, a relic of a lost time?

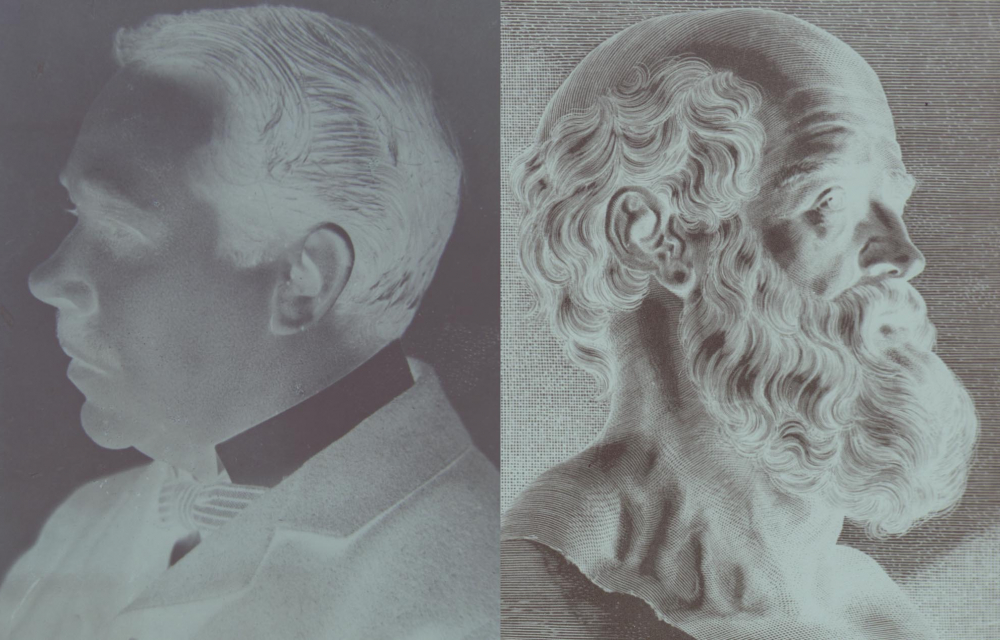

It is precisely this question that is explored in the Swedish classic Doktor Glas (1905), written by Hjalmar Söderberg. It is a novel worth reading, if only for the fact that Söderberg's shimmering prose often eclipses its lack of philosophical depth. The narrative follows the turbid inner life of the main character, doctor Glas, glimpsed through the lens of the scribbles in his journal. A recurring theme in the novel is the Hippocratic oath. But this is only one of the many ethical issues that bubble up in the novel. In just over a hundred pages, the author manages to shoehorn every imaginable bio-ethical dilemma in an otherwise sparse plot: abortion, euthanasia, medical malpractice, trolley-problems, freedom of conscience... All of which are brought up – only to be dismissed out of hand. They are but illusions. Any and all values are revealed to be empty, vapid, vitreous.

The most unfortunate choice in the novel, I think, is the character of doctor Glas himself, portrayed as a splenic misanthrope on the fringes both of sanity and society. What makes Söderberg's novel interesting, however, is precisely the opposite observation: it puts its finger on the phenomenon of the modern doctor freed from the shackles of ethics, rather than any particular individual. What was just becoming thinkable at the turn of the century – a doctor to whom the oath is nothing but a convenient lie (or, to use a fashionable idiom, "a social construct") – is now standard practice.

"Doktor Glas bares witness to the first glimmerings of this process of erosion. A century later, we can observe the completed deflation of the previous picture of reality."

The Oath was abolished in Sweden in 1886. The reason for its abolition was that it constituted an obstacle to the experimental ethos of modernity. The stagnated norms of medical practice were seen as "so much froth, nonsense from a bygone age" (in the words of one philosopher). The new requirement for the medical profession, it was decided, was to keep the doctor's practice within the bounds of the current legislation. The metaphysical richness of medicine, which characterized the medical schools of the past, was replaced with blind compliance to the bureaucratic machinery of the state. Doktor Glas bares witness to the first glimmerings of this process of erosion. A century later, we can observe the completed deflation of the previous picture of reality.

None of this, I should stress, has anything to do with the particular psychological or moral character of medical practitioners. There is, however, a sense in which we are all doctor Glas. One can find a collective consensus that the duties of the medical practice are nothing other than statutes of a social contract. The doctor's role is to carry out the legislative vision. In a bygone age, medicine was embedded in a cosmic perspective: a view of the world where values about what is good and what is evil were inscribed in the very texture of the world. In the present, these same values float groundlessly, with no justifying reason other than consensus and convention. As long as this remains the case, any rhetoric about "human dignity", "inviolable human rights", and similar slogans, rests on an extremely fragile surface.

Lapo Lappin is a philosophy student at Uppsala University. (Photo: Lina Svensk)